Displacement, Trauma, and Resilience: Connecting Their Eyes Were Watching God and “Chronic Disaster Syndrome” in Post-Katrina New Orleans

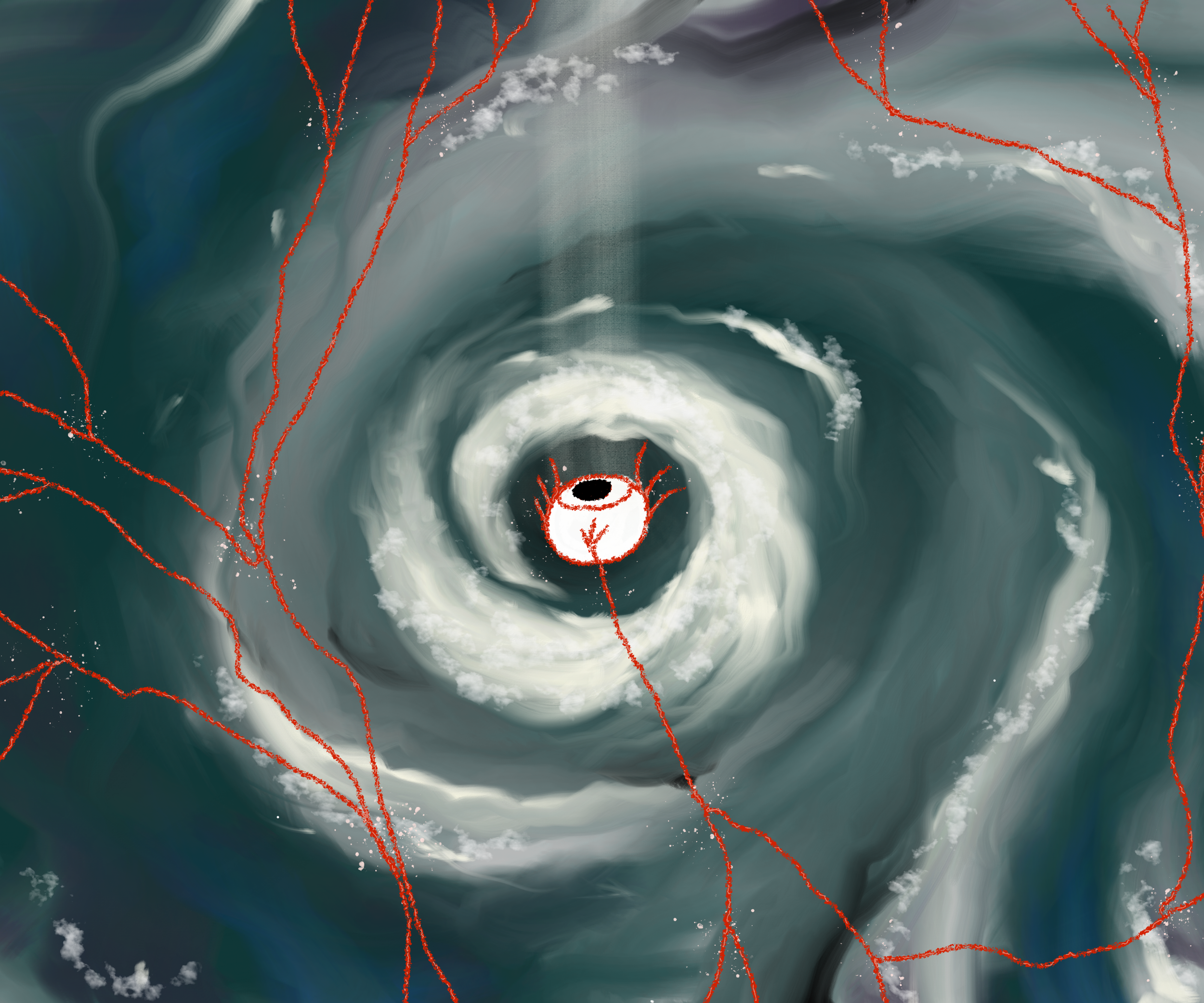

In both Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and the article "Chronic Disaster Syndrome: Displacement, Disaster Capitalism, and the Eviction of the Poor from New Orleans" by Vincanne Adams, Taslim van Hattum, and Diana English, themes of displacement, trauma, and systemic injustice are key to understanding the lasting impact of disaster. Hurston’s novel focuses on the personal and emotional effects of upheaval on Janie, while Adams and her co-authors examine how Hurricane Katrina’s aftermath in New Orleans created ongoing trauma, shaped not only by the disaster but also by political and economic forces that continue to harm vulnerable communities. Both works highlight how personal and collective trauma, displacement, and systemic injustice are interwoven in Janie’s journey, the aftermath of the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane in the novel, and the experiences of New Orleans residents after Katrina.

In their article, Adams, van Hattum, and English define Chronic Disaster Syndrome (CDS) as a complex condition resulting from the confluence of three phenomena:

… long term effects of personal trauma (including near loss of life and loss of family members, homes, jobs, community, financial security, and well-being); the social arrangements that enable the smooth functioning of what Naomi Klein calls ‘disaster capitalism,’ in which ‘disaster’ is prolonged as a way of life; and the permanent displacement of the most vulnerable populations from the social landscape as a perceived remedy that actually exacerbates the syndrome (Adams et. al).

The authors argue that in the case of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, these three elements—displacement, trauma, and systemic forces—combined to create a persistent state of psychological, physiological, and social distress. The trauma caused by the storm and subsequent flooding was not just about the physical destruction of homes and infrastructure; it was made worse by a political and economic response that prioritized private recovery efforts over public welfare, deepening the suffering of the most vulnerable, particularly Black and poor communities. Similarly, in Their Eyes Were Watching God, the trauma following the Great Okeechobee Hurricane of 1928 is felt not during the storm itself, but in its aftermath. For Janie and Tea Cake, the emotional toll comes later. Tea Cake had to be “part of a small army that had been pressed into service to clear the wreckage in public places and bury the dead,” which leads to greater psychological trauma post-disaster, rather than during (Hurston 170). For Tea Cake, as a Black man, the recovery process is shaped by his position in a racially and economically marginalized group as he has to literally throw away the bodies of people that look like him in a “big ditch” (170). This disregard for Black bodies causes the emotional trauma that is separate from the hurricane, but exactly what the CDS article describes in discussing the post-trauma of a disaster, without a name for it existing in Hurston’s narrative.

Furthermore, one of the defining features of CDS is its ongoing nature: residents were not only displaced physically by the hurricane but also by political decisions that hindered their ability to return to their homes or rebuild their lives. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, many poor and Black residents were forced into temporary shelters or FEMA trailers, which were often located far from their communities and lacked adequate resources. Even after years of recovery efforts, people “were able to return to New Orleans but… were not able to move back into their homes, who remained in FEMA trailers or rented spaces for several years or more, and who told us they were experiencing ongoing “displacement” in the sense that their lives had not returned to normal, even though they were back in their ‘place of residence’,” (Adams et. al). As the article notes, the displacement of New Orleans’ poor communities became not only a symptom of the disaster but also a result of the “deliberate and permanent eviction of the poor” from the city, driven by forces of “disaster capitalism” that further marginalized the already vulnerable populations (Adams et. al). This connects to the struggles Janie faces in Their Eyes Were Watching God as her and Tea Cake’s home is destroyed in the hurricane, and they are forced “back on the muck. They worked hard all day fixing up a house to live in,” without help from anyone because of not only the racist society they live in, but because of the lack of resources to support them, like the “disaster capitalism” concept explained in the Adams et. al article (Hurston 172). Even though Janie and Tea Cake find themselves out of harm—to their knowledge, immediately after the hurricane—they are still left without a home nor financial support, and are stuck in a state of displacement. They must rebuild without any help, and the political decisions mentioned in the article apply to Janie and Tea Cake tenfold, especially as the novel takes place almost a hundred years before Katrina, with significantly less government support for anyone, let alone people of color.

Displacement is a complex trauma that affects marginalized people in different ways. For Janie, her emotional and social displacement is tied to her relationships and society’s expectations of women, especially women of color, particularly before the hurricane and in her early life, when she has to be married as “sixteen” because it is what is expected of her by the other women in her life (Hurston 11). In New Orleans, residents face compounded trauma from losing their homes, jobs, communities, and support systems. In both cases, the inability to return to life as it was before the disaster shows how trauma lingers. For New Orleans residents, the effects of CDS are physical, social, and psychological. Many, especially those who were separated from family or evacuated, experienced long periods of isolation, leading to mental health issues like PTSD, anxiety, and depression. The destruction of neighborhoods and loss of community support made these problems worse. Similarly, Janie’s trauma is shaped by the emotional upheavals in her life as each of her marriages brings a new form of suffering, and she experiences deep psychological displacement as she loses herself in these relationships. The need to kill Tea Cake, when he finally succumbs to the rabies he contracts during the hurricane, represents a trauma disconnected from the disaster itself because Janie has to kill man that represented her freedom from society’s expectation, as well as her salvation from her past toxic relationships — even as Tea Cake is abusive, as well. She is unable to return to life as it was because of the hurricane destroying her home, but also a side effect of the storm leading to her partner’s death.

The trauma experienced by Janie, much like the trauma experienced by the residents of New Orleans, is not easily healed. Both narratives illustrate how the psychological effects of disaster—whether personal or collective—cannot be neatly resolved, and healing is often a long, painful process. Janie’s resilience echoes the endurance shown by New Orleans’ residents, who, despite the psychological and physical scars of their displacement, continue to rebuild and reclaim their lives, often in the face of systemic neglect.

In the case of New Orleans after Katrina, the concept of "disaster capitalism" is used to describe the exploitation of the city’s devastation by private corporations and political elites, who used the disaster as an opportunity to profit from reconstruction while sidelining the needs of the poor, predominantly Black communities. Adams et al. describe how government-led recovery efforts, which were supposed to address the needs of the displaced, instead prioritized private sector interests, leading to the permanent displacement of many residents. Housing that had once been affordable and accessible was replaced by luxury developments, and the public infrastructure that might have supported community rebuilding was often neglected in favor of privatized solutions. The result was a form of "false recovery" where the rich and powerful benefitted, while the poor were displaced not just physically, but from the very fabric of the city they had once called home (Adams et. al).

Thus, the themes of displacement, trauma, and systemic injustice are central to both Their Eyes Were Watching God and the article on Chronic Disaster Syndrome in post-Katrina New Orleans. Both works illustrate the ways in which personal and collective trauma are shaped by larger social, political, and economic forces, though Janie’s journey in Hurston’s novel is through forced independence, as her community — which is essentially just Tea Cake — crumbles when she is forced to defend herself when he contracts rabies. Her personal trauma, and at a point, collective trauma with other Black residents in Florida, mirrors the Chronic Disaster Syndrome presented in the article, even as they take place decades apart.

References

Adams, Vincanne, et al. “Chronic Disaster Syndrome: Displacement, Disaster Capitalism, and the Eviction of the Poor from New Orleans.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Nov. 2009, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2818205/.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Their Eyes Were Watching God. Perennial Classics, 1998.